After a girl I like tells me that she cannot be somebody’s person, I am sent into an intense period of introspection. I am a dreamer, and everybody dreams, anyway. And in these dreams of mine, even in the dreamy motions of life, I take the world for its personality. I take people for their words, for their warmth. And I like to think that everyone is as sensitive as I am, that everyone takes things to double-heart, that everyone swallows the world in tiny gulps to savor the flavor. Or to keep life moving on along. What does it mean to be somebody’s person? What does it mean when I’m not allowed the opportunity to savor?

In the airport, stumbling around on three hours of sleep. Walking into the women’s bathroom, where empty mirrors lead to one woman and her reflection, blasts of hairspray coating her hair and landing on the glass, red lip deeper than the hue of her hair, ignorant to me, who is stupid, watching, wondering who, what, led her here. I can only watch for a moment, until I am drawn to fix up my own reflection. Looking into my eyes while the mirrors now lead to both of us, I trigger a tiny moment of pain. I will never know anybody’s story if I can’t get a hold of my own.

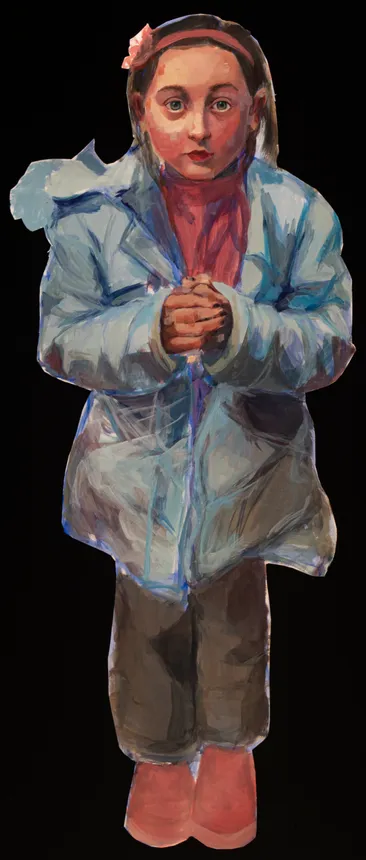

On the plane, after I’ve folded myself into a pretzel by the window, a little girl with hair and skin and fear like mine shimmies into the middle seat. I glance at her, and I see myself in this child I will never speak to, her eyes focused on what’s in front of her, afraid to venture her gaze left or right. I imagine the plane breaking at its wings while the attendants mime to nobody. I imagine that I would shield her from debris. I imagine I would save me, be somebody’s person.

I’ve been somebody’s person before, not in the way I would have liked to be. Who I wanted to be was erased as soon as we came in contact. I was somebody’s person, but I wasn’t me. I was an enigma,a driving force, a vortex and a black hole. I was draining and being drained, demanded and pushed away. “Loving someone,” she started, after hyperventilating on the phone with me, “loving you is like I’ve given you a gun. And I’m just waiting for the gun to go off.” And I didn’t know what to say. I never know what to say.

At lunch with my father, the day warm and stuffy with clouds. He tells me what he is afraid of as we accidentally knock against each other in the basket of fries. “How’s your mom doing? You know, with everything. Losing her mom?” I am waiting for him to ask me how I’ve been doing, but nothing is like losing a mother. That’s everybody’s first person. “I don’t think I’m ready for that, you know? Do you know why?” He reaches for another fry.

“Because you’d feel guilty.” I bring my knees to my chest on the stool.

“Exactly. You know why?”

“Because you aren’t close.”

He nods and gets up to find some salt. He’s always been like this—he’ll spill a grave thought or detail into the river of our conversations, riddle them with black, iridescent oils, and get lost in the beauty of the spill. And I never mean to, but I always get stuck in that oil. I start to wonder who he is in there, in that mass of guilt and muscle and fear and sweat. And I like to think that everyone is struggling in some secret, unimaginable way, and I’m always trying to figure out how. What has happened to you? I want to know what happened to him. When he returns with the salt, he starts talking about a new movie on his watchlist, and I participate, but I am stuck in that guilt he poured.

Whenever I see my brother, he is leaving. He’s always late for something. And he’s in college now, and we can’t be close like we used to be, and I don’t see him like I used to. He’s always halfway out the door, never afraid to say goodbye but always afraid to savor the leaving. I always make him hug me before he goes. Off to work, to school, to taste the world in secret. I worry it makes me childish, how much I wish we were best friends again. It makes me childish to think I could be somebody’s person.