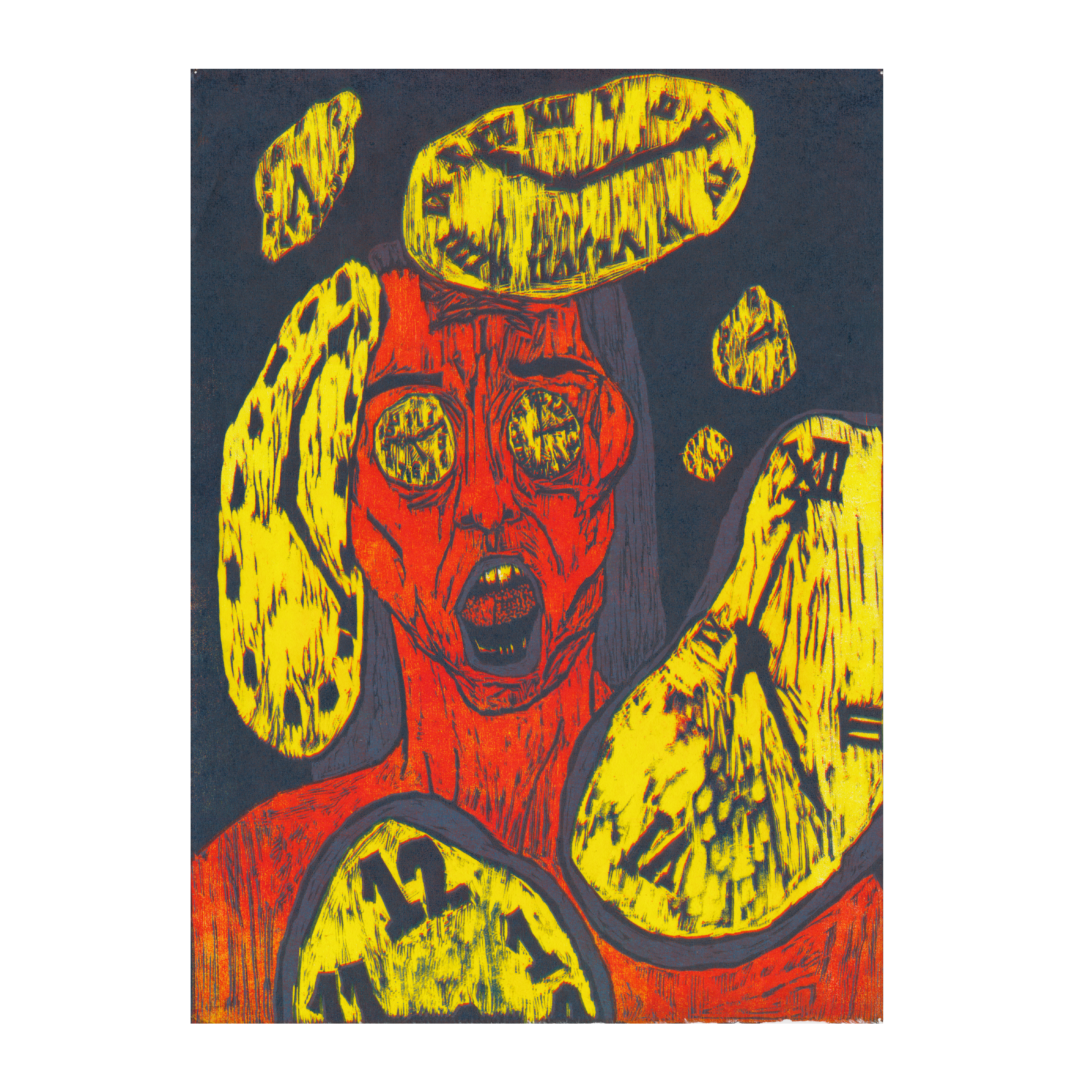

On a walk that could not have been longer than twenty minutes, I came across a graveyard. This graveyard was not filled with rotting corpses or skeleton-men or headstones of truth-stretching titles, but instead, it was filled with bottles. There were green glass bottles, shattered shards of translucent yellow, mini flasks half-filled with golden blood, and brown-bagged cans crushed by a fistful of finality. This graveyard– a cemetery of alcoholic lineage– reeked, not of rot, but liquid luck and an old New Orleans bar. The eerie silence of a dead ecosystem spread across the land because no creature lives for a belly-warming Fireball or a chilled Bud Light or a nightly “red-rum” (as my mother called it) like men. Alcohol was made for men by men, and a philosopher might say this is true because humans are the only beasts on earth that must live with their own consciousness in painful, unfathomable awareness. However, I am not a philosopher. I am a deer in headlights and the daughter of an appointed alcoholic, so I must say, with full clarity and a voice I have trained to be steady, that alcoholics are only alcoholics to strangers. My father was an alcoholic to his AA sponsor and the woman at the front desk of the rehabilitation center and, for a while, my mother. But to me, he was never such a thing. He was a beanstalk man with a scratchy face and a sturdy, flat chest. He was a gentle guy who was tall enough to poke his head through storm clouds and count the miles between lightning and thunder. He was a guitar-strumming, Nirvana-singing, car-loving, late-night TV watching man who would weep when I wept and snort when I laughed. To me, he was never a sad drunk or a tipsy driver or a struggling man in need of help. He was my father, and on that walk through the graveyard filled with train-track garbage and the scattered remains of tequila bottles and beer cans, I was not the daughter of, the niece of, the cousin of, or the friend of an alcoholic. I was myself– the child of a beanstalk man, a deer in headlights.